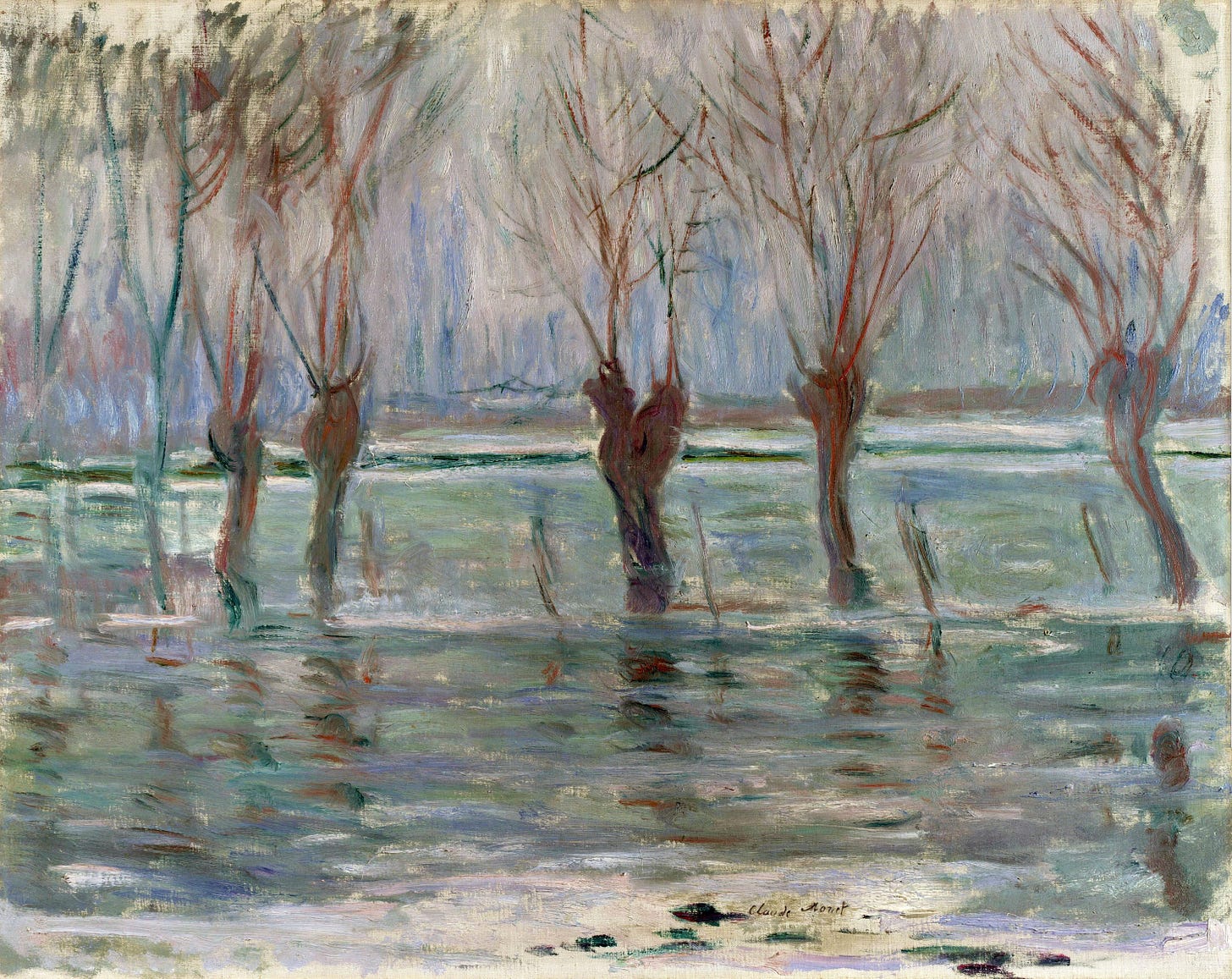

“Flood Waters, 1896” Claude Monet

Poets [and artists] are “makers, craftsmen: It is given to the seer to see, but it is then his responsibility to communicate what he sees, that they who cannot see may see,” Denise Levertov

The scene outside the car window startled me. Dark flannel gray skies, filled with low hanging angry clouds, holding a howling wind close to the ground. Barren January trees fighting to remain upright, and chopped ice in the frozen river beneath the bridge we were crossing. I shivered and moved closer to my new husband. I hadn’t noticed the river when our plane landed, although we taxied to the end of the runway that nearly touched the water’s edge. We had flown into Harrisburg, Pennsylvania from West Texas to visit his family. Married just two months earlier, we were still coasting on love and the adrenaline of a fast romance, followed by an overnight honeymoon. I glanced back at the scene outside the car and whispered to him, “Look, the water is raging beneath the ice. Such a hostile, unfriendly river.”

He smiled and squeezed my hand, reminding me that it’s “just a body of water. It has no intentions.” Still, I had never seen a river moving so fast that even the ice could not hold it back. I buttoned the thin corduroy jacket I was wearing, pulling it tight around my shoulders, wondering how people in the northeast survived the long winter months. Most of my life had been spent in the west, California and Texas where water was in short supply. There were no swollen, fat rivers like this in West Texas, where rainfall was so sparse, farmers prayed for it to appear and depended on irrigation systems to grow crops. As we pulled away from the bridge I looked again and shivered, thinking, we couldn’t get away from the water fast enough.

Rivers are powerful symbols in literature and works of art, representing the passage of time, fluidity of life’s journey, and the internal landscapes of human emotions. Flooding rivers are the topic of myths, folk tales, fairy lore, and sacred stories. In the Judeo-Christian faith, the most famous narrative about the power of a river to defy containment by the ancient land that surrounds it and inflict harm is the Genesis Flood story. But not all flood tales are filled with frightening descriptions of cataclysmic horrors that leave us fearful of a powerful God.

Indigenous stories honor the presence of a divine spiritual essence in water, an idea that’s deeply embedded in the collective unconscious of the people who carry the tales. The Ojibwe Myth of Turtle Island tells of the Great Spirit’s call to the muskrat to save the earth during a flood by diving into the waters in search of land. The muskrat discovers a great turtle swimming beneath the waves, which becomes the foundation for a new land where the Ojibwe people can exist. This creation myth expresses the belief in “intricate ecological relationships between the environment and all things.”

Five years after my encounter with the Susquehanna River and my instinctual response to its power, my husband and I moved our little family into our first home, a green colonial townhouse, in a town about twenty-five miles away from the river. Just close enough to drive to the banks for the annual fourth-of-July fireworks, but not so close that I felt threatened. As a transplant, I struggled to cope with the humid air, so cold in the winter, it felt like a knife to my bones and so heavy in the spring, it held pollen close to the earth, stirring up my allergies. We settled into our new home, the four of us: me, my husband and two little boys. Soon, we added a fifth member, a black Scottish Terrier, a rescue named “Mr. Magoo.” We bought our first new piece of furniture, a sienna-red sectional sofa for the living room and I grew marigolds and planted a vegetable garden in the back yard. In early summer, the mulberry tree whose branches hung over the back fence dropped berries on the ground, drawing the attention of my two-and a half-year-old son, who rushed out the kitchen door in the mornings to grab a handful and shove them into his little mouth. Life was Edenic, peaceful and good.

When the baby was five months old the storm hit. Tropical Storm Agnes clambered up the eastern seaboard in June 1972, turned inland and stalled over the mid-Atlantic states dropping between 12-18 inches of rain area in four days. The heaviest rainfall occurred in just six hours, causing the 444-mile-long Susquehanna River to crest at 32.57 feet, almost 15 feet above flood level.

Local journalist Cal Turner described it this way. “The river climbed with utter abandon, moved rapidly into city streets. It tugged at the underpins of the big bridges. It pulled boat ramps and docks apart, it began knocking homes aside, flipping cars over, settling in to stay. It took lives without even a faint gesture of mercy. Power lines went out, traffic stalled and by nightfall the area was one, big wet sponge. And the rains stayed, and the river climbed. And raced along.” His words affirmed my initial suspicions about the river’s potential to cause harm. This was a dangerous flood that cut a deep gouge in the memories of everyone in the area. But as I look back at the experience, I wonder if it was carrying a message to me. One that I failed to see at the time.

Over 340 million years old, the Susquehanna is older than the land that surrounds it. Its 28,000 square mile watershed drains across 275 acres of farmland, emptying into the Cheaspeake Bay. Because of its rocky bed, composed of shale, limestone, and sandstone which forms long rock ledges in some areas and sculpture-like rock formations that emerge when the water table is low, the river is almost unnavigable. The Susquehannock and Lenape peoples who settled on the river’s banks believed it to be a living entity and gave it the name, Susquehanna, derived from an indigenous phrase meaning "mile wide, foot deep." Its shallow bottom is believed to have been a contributing feature that led to the 72’ Flood when rain falling at such a high rate could not be absorbed by the riverbed and water built up so quickly, it could not be contained.

Movement is essential to the ability of rivers to support all of life. They “carry large quantities of water from the land to the ocean, where the seawater constantly evaporates and forms clouds. Clouds carry moisture over land and release it as precipitation…which completes the water cycle, feeding rivers and smaller streams. But, when the water table is breached and a river floods, it has an unstoppable power to tear through the surface of land and cause widespread damage. In recent years, we have come to see how floods expose social inequality, as waters penetrate the infrastructure in poorer communities, putting residents in harm’s way.

As a people trying to survive in a capitalistic culture, driven by exploitation and extraction, our response has been to design systems to control floods. Often, they mitigate damage by managing water movement, redirecting it away from populated areas. Ecologists say we have mis-read rivers, treating floods as encroaching upon the infrastructure of our civilizations, when the truth is far simpler: it’s a body reminding us that it once was free to move, unencumbered by the arbitrary borders established by our species. Lately, scientists and academics have shown interest in the ecological wisdom carried in the legends of indigenous cultures, which focuses on a more complex, layered understanding of floods. One is the Cherokee origin story that conceives of the earth as “a great island floating in a sea of water and suspended at each of the four cardinal points by a cord hanging down from the sky vault. . . .When the world grows old and worn out, the people will die and the cords will break and let the earth sink down into the ocean, and all will be water again.” This myth captures the animacy of the Earth and places human beings in a supportive role as participants in the cycle of life, challenging our patriarchal notions of control by reminding us, “we begin in water, and we return to water.”

Writers use water and its physical elements as metaphorical devices to create images that illustrate the struggle of a character facing the powerful flow of destiny. Some use the river as a threshold which, when crossed, brings about dramatic change in the life of a character or community. Artists who once portrayed the strength, beauty and power of rivers have moved to create a shared artistic language that extends beyond aesthetics to support a growing awareness of climate change, sustainability, and water scarcity. If floods expose our vulnerability and systemic inequality in the world, perhaps, they also call on us to use our imagination to create forms of self-expression that at once help us cope with uncertainty and promote awareness of our reciprocal relationship with the Earth.

Water has always been a powerful symbol, seen for both its life sustaining elements and its connection to the sacred. In ancient history, river valley civilizations are considered the most important phenomena, especially those that “emerged along the fertile banks of the world’s great rivers [and] laid the groundwork for the complex tapestry of modern human culture,” including the development of agriculture and the resulting stratification of society. In contrast, other cultures have honored the spiritual dimensions of rivers as having divine significance. In many, water symbolizes fertility and childbirth. “For example, in ancient Egyptian mythology, the goddess Isis was often associated with the Nile River, which was seen as a symbol of fertility and abundance.” All of this causes me to wonder if my own strong reaction to the frozen Susquehanna River the winter day we rode across the bridge was the expression of a natural awakening in my body, a signal from the anima mundi, the soul of the world, calling to my future self as a mother who would not only bring new human life into the world but also gather new stories about my ancestors. At the time the feeling was murky, undefined. But it was undeniable.

The weekend of the Agnes Flood of ‘72 was bad. No one anticipated the widespread damage, done to the valley when the waters rushed over the riverbanks, filling the streets of the capital city and flooding mansions that lined the river. Up and down the entire length of the river, towns and villages were hit with devastating discharges of water, ravaging and paralyzing the region in the worst flooding in 36 years. “650 billion gallons of water gushed through Harrisburg, where the normal river volume is 23 billion gallons a day.” Nearly 70 thousand homes were damaged, and the loss of life was shocking. Environmental sciences professor, Andrew Stuhl called the storm a “benchmark, a warning and a cautionary tale of what it is like to live with rivers.”

Twenty-five miles away, in our cozy home, we lost electrical power and water. On Sunday morning my husband joined neighbors who drove to the local water plant to fill bags with sand and stack them around the perimeter to prevent further damage. When he arrived home late in the afternoon, we opened a bottle of wine and ate sandwiches for dinner. We sang songs to the boys and put them to bed. Unable to sleep, I decided to get out of bed and paint a small bureau to match the baby’s crib I had covered in robin’s egg blue a week before the storm. My husband and I pulled the bureau onto the second-floor landing, set it on newspaper we spread across the floor, and I sat down to paint. Two glasses of wine and two hours later, I grew tired and decided I’d done enough for the night. So, I carefully placed the lid back on the can of paint—-which was about one-quarter full. Not wanting the lid to stick to the top, I pushed it gently back down on the can and left it sitting in the middle of the floor. Tomorrow, I thought. I’ll finish painting and maybe we’ll have water again. We did not. In fact, water wasn’t restored for another three days.

The next morning, sunshine broke through the bedroom window, announcing the end of the storm. Today, we can celebrate the end of the flood, I thought. I considered staying in the comfort of the bed a few more minutes until, in the background I heard the voices of my husband and two and a half-year-old son. “Mommy is not going to like this,” my husband said. His tone was tender but firm.

“Yes, yes, she will,” my little boy responded. “Look here Daddy. I painted birdies on the wall.”

“Oh, my,” his father said. Their voices grew fainter, and I imagined they were descending the stairs to the first floor. I got out of bed, threw on my bathrobe, and walked to the top of the stairs where I saw what appeared to be large birds, painted in robin’s egg blue on the walls.

“See, Daddy” Jason said. “I painted the TV, the books and even the couch." Mommy will love this. I did this for her.”

Slowly, I walked down the stairs, imagining what I’d find. When I got to the living room, the dark sparkling eyes of my child greeted me. His smile was that of a young master who was pleased to show off his work. “Look, Mommy. Look. I painted for you.”

What could I do. He was so elated. My sweet son. I adored him, his bubbly, happy countenance his fast-moving little body, the spirit that ran beneath the surface of his deep brown-almost-black-eyes. Years after the flood of ‘72, we realized he had inherited his grandfather’s gift for painting. As he grew into a young man, we could see his innate creativity. Drawings on paper napkins as we sat in a restaurant waiting for a meal, his eye for detail, sensitivity to color and composition, as well as his gift for capturing ideas and emotions in visual form. I watched with wonder, as the artist emerged in the son who carried my love of narrative and art.

Like thousands of other families, we cleaned up after the Agnes Flood. Our water wasn’t restored right away so we weren’t able to get the paint off the new sofa. We couldn’t save the television and were not able to remove the paint from about a dozen books. We set them out for collection with other belongings destroyed in the storm to be picked up by the borough sanitary department. Weeks later, we repainted the “birdies on the wall,” covering up my son’s first creation. When I remember the losses we had, I am reminded of Andrew Stuhl’s words about the emotional impact of the flood on residents in the Susquehanna Valley. He spoke of a pervasive sense of distress, saying residents “lost things that they could never replace. It wasn’t the material possessions, but the sentimental things like photo albums and dad’s military uniform – things that meant so much and yet seemed to be taken away in an instant.”

While other families were experiencing trauma and loss, mine remained safe and, as the river rose beyond its banks and flooded the land, I watched a life awakening; the life of an artist, a little creator who was making magical memories. The story of my son’s “birdies on the wall” painting became the theme of my family’s flood experience. Sharing the story over the years has altered my idea of the flood, changing it from that of an environmental disaster to an event where the river came alive. Not only does this affirm my belief that humans are “active participants in shaping reality through art,” it gives me insight into author and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s notion of the use of interpretive work as a form of “natural medicine,” or restitution for the damage human beings have imposed on the environment. Creating stories and art about Mother Earth makes us “partners in renewal,” rather than victims.

This notion may have been beyond my toddler’s ability to understand, but, even as a very young child, he displayed an artist’s gift for imaginatively interpreting the events in his little world. He was too young to fully grasp the impact of the flood, but he’d heard his parents and neighbors talking about disaster for days and, perhaps without realizing it fully, responded to tales of loss by creating life in his art. His painting of “birdies on the wall” helped us see the world differently.

Over fifty years later my artist-son has a young daughter who is also an artist. Her paintings and drawings awaken my sense of interrelatedness to the Earth, affirming my bond to the Susquehanna River whose waters flow with a power like the blood that courses through the veins of my family. As the youngest member to carry on the mission of helping to restore soul to the world through art, she belongs with us. Carrying and writing these stories about my family is my way of honoring the call to create and, as I recount this one, I wonder if the spirit of the river touched this desire on a subconscious level when we came across one another so many years earlier. Had the Susquehanna River been able to speak, I wonder if she might have told me this story. I wonder if I might have listened.

If I learned anything about surviving the ‘72 Flood, it was this: In my family, we are artists and story carriers. We see stories everywhere and we bring them to life in narratives, paintings and in other creative ways that both witness suffering and give voice to all living beings. This is the art of the flood.

Below is a picture of the bridges over the Susquehanna River, painted by my son’s grandfather, Samuel Hollinger, in 1968, four years before the flood.

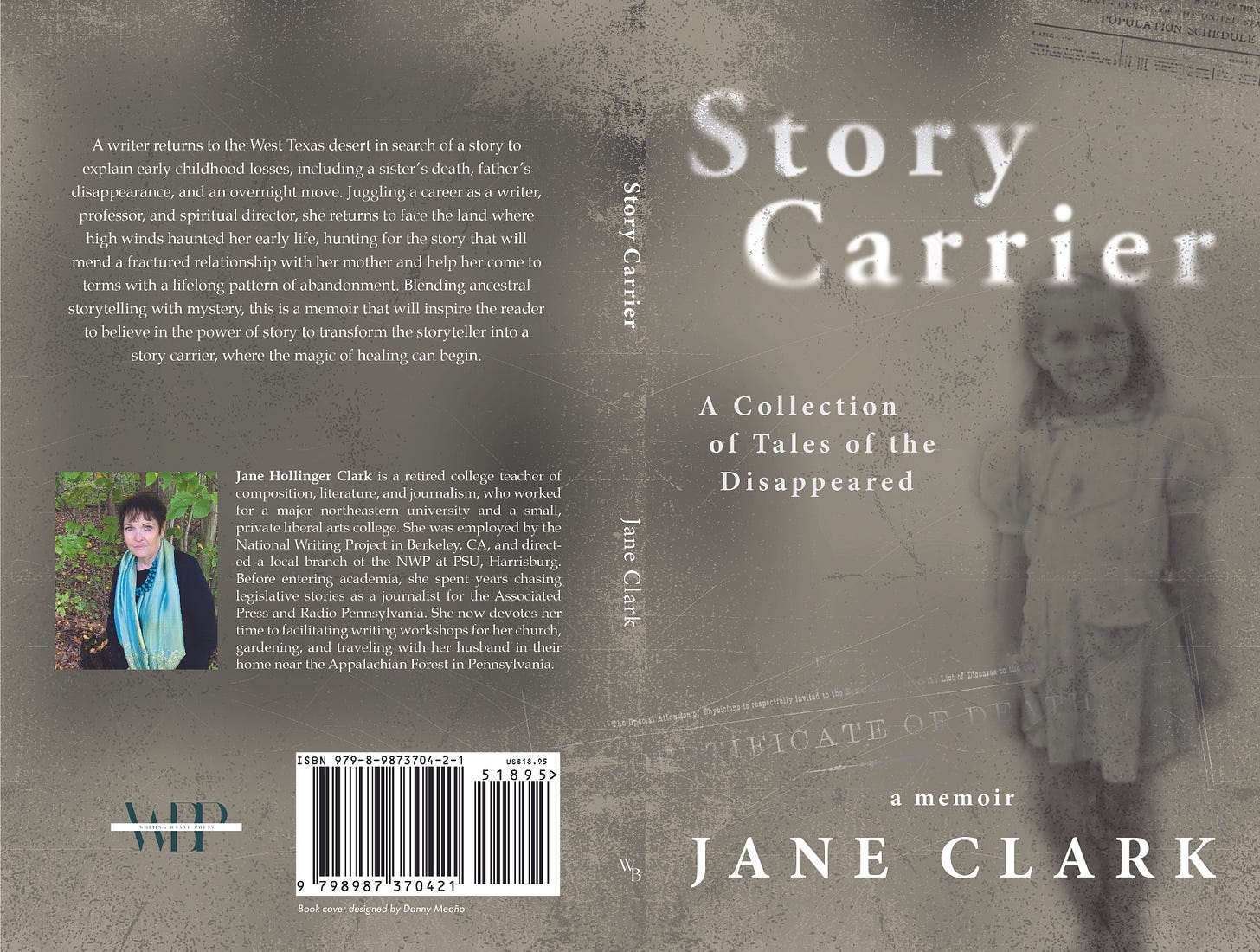

To read more about my life as a carrier of stories, follow me at Story Carriers: The Movement. My book, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared, is available here https://a.co/d/09CV7xtq

The child's abstract painting above was created by my granddaughter when she was younger.