Tending the Spark

When Art is a Form of Protest

The summer of 2025 seems to be the year the world will burst into flames and burn to the ground. In America we’re watching an increase in attacks on civilians by a fascist regime using terror to overwhelm and subdue us into a state of silence and acceptance of rule by a wealthy class. Last week’s incursion by ground troops moving into Los Angeles as part of the strategic buildup of military presence in the city was a show of force to both manufacture chaos and generate support to deport immigrants living in the state—even those who have the right to be here. The images of occupation hit me hard. I didn’t live in LA, but California runs in my blood—the sweet smell of peaches ripening in orchards and grape vineyards of the north, the stretch of fields where stories grow under the sun. And yet, when I saw armored trucks roll past murals in East LA, it tugged at something deep in me. Not just fear, but longing. As if the California I knew as a young woman—the one that taught me to see, to listen, to speak—was calling me back to bear witness. And to remember early lessons about violence as a tactic of control.

In the late 60s, in my northern California high school, I learned about the power of art in response to brutality and inhumanity under the training of my teacher, Mr. Montoya. He didn’t lecture about history or demonstrate craft; he conjured, sharing stories about oppression and violence. Long before he became a celebrated artist and poet, Jose Montoya shared stories with his students about his work with the United Farmworkers Union in southern California, where seasonal pickers struggled to survive the heat of the sun and harsh working conditions. He taught us about another America, where the wealth of landowners swelled on the backs of a hardworking class of people whose wages were so low, they barely survived. Sitting quietly in his classroom, I painted while his voice filled the room and before I knew it, brushstrokes fell in line with his memories, and shadows seemed to form clouds of resistance on the canvas. I sensed that what he offered us was more than creative technique—it was a way to survive what the world might throw at us.

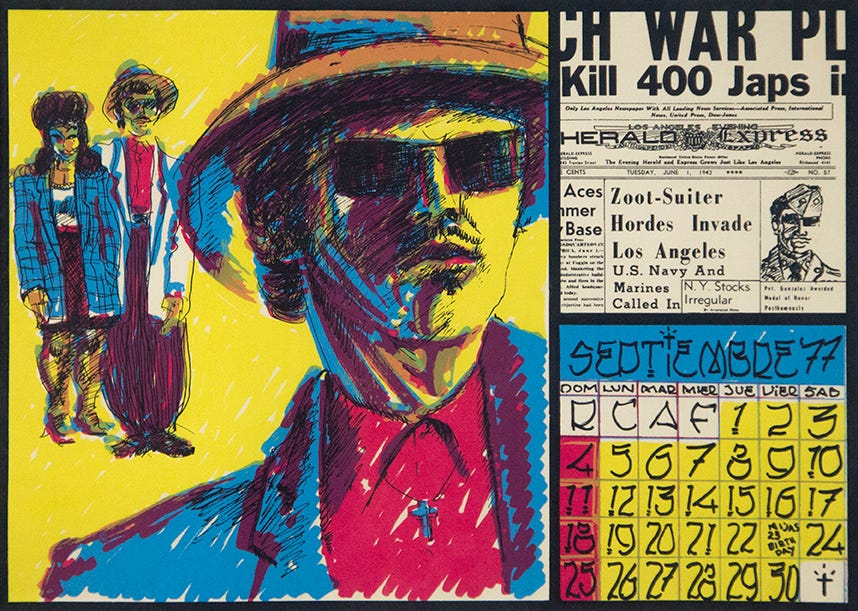

Montoya’s work from the Art Collections & Archives | Sacramento State (csus.edu)

What the world threw next was Vietnam. My stepfather, a military pilot, was training to fly Puff the Magic Dragon—an AC-119 gunship that rained fire from the sky. On a Sunday afternoon in October, my three siblings, my mother and I sat around the dining room table, while he played a recording of the mini-guns firing. It didn’t sound like war; it sounded like erasure. I was horrified and yelled, calling him a monster. My voice cracked. Not from fear, but from becoming. A young woman, I was beginning to feel the edges of my voice. He spoke like a warrior, carrying a different story about a mission to protect a fragile nation from collapse under the threat of communism.

Photo of AC-119, Ghosts of the Battlefield

In those years, I came to understand that violence and art are not strangers—they often inhabit the same quarters. My stepfather was both a soldier and an artist—a painter, a writer—and he carried more than ammunition into the war. He carried a sensitivity to truth that placed him at odds with the machinery of destruction. Though he volunteered for the mission in Vietnam, even he seemed staggered to learn that the war would claim nearly four million lives, half of them civilians: farmers, women, and children. At night, he wrote letters in passages as intimate as they were unflinching. He described the soundscape of war—the thudding guns, the low roar of planes skimming the fields, the shells echoing across rice paddies. The rhythm embedded itself in him, reverberating like the meter of a stanza, each blast a beat, each silence a line break. War and poetry became inseparable, one haunting the cadence of the other.

By the time he returned from the front, he was nursing deep moral and emotional wounds caused by the firsthand devastation of combat. And his role in it. He spoke openly about his disillusionment and grief-filled guilt. Eventually, he turned to art, channeling his angst into designing and building--by hand—a passive solar home in the desert of West Texas.

Working alongside my two brothers and a few migrant workers who had crossed the border from Mexico, he made enough adobe blocks to build a three-bedroom home. Building, literally, with the same hands that once contributed to destruction. The tactile connection to the earth, the collaboration with people who had escaped political oppression—allowed him to reclaim something that the war had fractured. Maybe it wasn’t just about building a house, but about constructing meaning, rebuilding something within himself that had been torn apart by combat and guilt. Not through grand statements, but through labor, touch, and shared effort. It was a form of quiet atonement.

Looking at his picture, with the brick in his hand, I am reminded of Jose Montoya, who began his life picking grapes as a child with his family. I remember his stories about working to stencil imagery on the walls of churches in the evenings. Like my stepfather, Montoya understood the power of art made by hand as a kind of weapon to educate and draw attention to the misuse of force to oppress. He understood art as a response to the violence used to extract labor out of vulnerable people. One afternoon as I sat, listening to his stories, brush in hand, spilling ochre and violet onto the canvas, I imagined the world that extended beyond the borders of the canvas. Beyond the walls of safety that surrounded the classroom. I listened, but more than that—I watched, and my perception of the world began to change. This wasn’t just a high school art class—it was a transformative experience.

José Montoya - Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia

When I spoke of my hatred of the war, Jose told me about his work with the Royal Chicano Air Force, a collection of artists who described themselves as freedom fighters dedicated to “translating the Chicano experience, life and culture into art expressions.” He explained how to use art to carve out space for rebellion while living in a nation that normalizes the ideology of expansionism and white supremacy.

Years later, as one of the nation’s best Chicano bilingual poets, he used poetry to illustrate the struggle of a Korean War soldier trying to reclaim his life. “El Louie,” was written in the voice of a young man using the image of masculine power to struggle against the forces of oppression and inequity.

“And on leave, jump boots shainadas and ribbons, cocky from the war,

strutting to early mass on Sunday morning. / Wow, is that el Louie.”

Over time, I cultivated a deep passion for narratives expressed through the voices of those muted by hostility, fear, and an unjust system that elevates some at the expense of those labeled as "others." In the company of the silenced, I began to sense their stories even before they found expression in words.

What I didn’t realize then was that I was absorbing more than history from these men. I was inheriting a way of seeing. The idea that art shapes awareness, that stories are vessels for change, settled quietly into my bones. Years later, as I stood in front of my own classroom, guiding students through the act of writing, of storytelling, and capturing life on the page, I began to see the lessons I’d been carrying. I felt the warmth of the fire burning deep inside me to nurture my students’ stories.

And now, as the world fractures under violence and uncertainty—as headlines scream, as conflicts deepen—I find myself returning to the worldview they instilled in me. The idea that chaos does not erase meaning. That violence intended to terrorize does not have to silence. That movement, whether on canvas, in farm fields, on battle grounds, in the streets, or on the page, holds shape. That stories, when lit with intention, restore agency.

It’s why I teach. It’s why I write. It’s why I help others find the contours of their truths. In the face of disruption, I hold onto the idea that creating is an act of defiance. It’s a form of confrontation and evidence that something about us will always survive.

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-jose-montoya-chicano-drawings-fowler-museum-20160218-column.htmlArtist José Montoyas voluminous drawings are an essential record of Mexican-American life - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

what a powerful and moving act of remembrance this is. Thank you for sharing 💔

Thank you for sharing this personal experience! What a contrast and deep exploration of so many complexities in our world. I’m going to reread this a few more times to absorb.