Malala Yousafzai: The Youngest Nobel Prize Laureate

Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been their in so much higher degree; the pen has been in their hands.

Jane Austen

I am thrilled to see you here after a long summer away from my column. I’ve spent the last two months working on “Story Carrier: The Movement,” promoting my book, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared, and writing a new book, Un silencing: A Workbook for Story Carriers. This post previews some of the themes contained in the book and will give you an idea about how important I feel it is for women to reclaim narrative control of our stories. I hope you enjoy reading it.

Two years after the Taliban shot Malala Yousafzai for her advocacy of girls’ education in Pakistan, she became the youngest person to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In her 1997 acceptance speech, she recognized her namesake, Malalai of Maiwand, who inspired the Afghan army to defeat the British in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Malalai is considered to be the Pashtun Joan of Arc, the young peasant girl who led the French army to victory over England in 1428. The stories of all three young women speak of their extraordinary courage, affinity for service, and deep faith. Joan and Malala continue to inspire social and political movements, but their lives differ in one way: Malala has been able to tell her own story in her book, I Am Malala. Joan’s narrative, so powerful it continues to draw followers, emerged in spite of efforts to silence her. The narrative journeys of both women stress the urgent need for us to tell our own stories.

Joan was tried and executed by the church in 1431, but it wasn’t until 1803, nearly 400 years later when Napoleon Bonaparte declared her a national hero. Another 100 years later, she was sainted. during that time, her life story was appropriated by historians, authors, and artists who adapted and reinterpreted it to fit various social, political, and cultural events. She became the subject of works by Shakespeare, Voltaire, George Bernard Shaw, Bertold Brecht, and Carl Dreyer who produced the 1928 film, “The Passion of Joan d’Arc.” Shaw’s 1923 play, “Saint Joan,” portrayed her as a tragic heroine who followed divine voices into battle. In his 1896 novel, Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, Mark Twain characterized her as a “semi-holy medieval figure and Catholic saint.” Although Twain considered it his biggest literary achievement, some criticized his zealous treatment of Joan.

One critic described the book as a product of Twain’s somewhat obsessive connection to the young saint. Wilson Carey Mc Williams describes his tone as “idealistic, uplifting, and at least vaguely reverential.” Ted Goia, the music historian, takes it a bit further, suggesting the portrayal is theatrical. He writes, “I suspect that this novel could even serve as the basis for a megahit movie in the current day, when studios seek out narratives featuring powerful female protagonists, sweeping cinematic panoramas and awe-inspiring effects.”

These cultural representations of Joan’s life show the power of storytelling to shape cultural and national identities. But they also illustrate the potential danger that fame brings to women: that of being objectified and losing control of the story. In Joan’s case, her image was used for positive purposes such as when it became the central motif of the suffragist movement, where it gave legitimacy to the fight to secure the vote for women, an effort considered impossible at the time. The British suffrage movement printed her image on banners and pins. As the namesake of the feminist Catholic organization, the St. Joan’s Alliance, her image frequently appeared on banners and flags at the head of marches. In Ireland, her story inspired the Irish revolutionary Maude Gonne, founder of the nationalist women’s organization, the Daughters of Ireland, who positioned herself as the Irish Joan of Arc.

Joan’s legacy was borrowed by the American suffragist movement when Inez Mulholland, a young labor leader and lawyer led more than 8,000 suffragists in a March for the Vote in Washington D.C. the day before Woodrow Wilson’s 1913 presidential inauguration. While she didn’t explicitly compare herself to the saint—photographs of the march show her riding a white horse wearing an elegant cape and gown. The press compared her to a Modern-day Joan of Arc, who rode into battle on a white horse, dressed in white armor in 1429.

The stories of these women evoke powerful feelings, and no one would question their value. But when official reports are used to foreground larger themes of courage and bravery, they often overlook more nuanced examples of women’s experiences, including complex feelings, and perspectives. In some instances, women’s stories have served the storytellers’ purposes, resulting in the perpetuation of misunderstandings and reinforcing popular stereotypes.

When Inez Milholland became the symbol of the American Suffragette movement, she was described as “the most beautiful suffragette.” But less was reported about Inez’ poor health which led to her at the age of 30, before the amendment was adopted. Her dying words, “Mr. President, how long must we wait for liberty,” was adopted as a rallying cry for the movement. Poet Edna St Vincent Millay wrote a poem memorializing Inez, which may have solidified her as an icon whose image and speech galvanized organizers to continue the fight.

Upon this marble bust that is not I

Lay the round, formal wreath that is not fame;

But in the forum of my silenced cry

Root ye the living tree whose sap is flame.

I, that was proud and valiant, am no more; —

Save as a wind that rattles the stout door,

Troubling the ashes in the sheltered grate.

The stone will perish; I shall be twice dust.

Only my standard on a taken hill

Can cheat the mildew and the red-brown rust

And make immortal my adventurous will.

Even now the silk is tugging at the staff:

Take up the song; forget the epitaph.

-Edna St. Vincent Millay

The treatment of Inez’ story should raise red flags for all women, for it reveals the way history can subsume our personal experiences and manipulate them to fit an official narrative.

For example, history glosses over the pressure on white women to turn their backs on women of color in exchange for approval of the amendment. It overlooks the key role played by journalist and suffragist, Ida B. Wells, who pushed for inclusion. Wells, who was asked to march in the back of the 1913 procession with the segregated contingent, refused, saying, "When I was asked to come down here [to Washington, D.C.,] I was asked to march with the other women of our state, and I intend to do so or not take part in the parade at all."

Her words foreshadowed the rest of the story. It was forty-five years later when the vote was given to women of color.

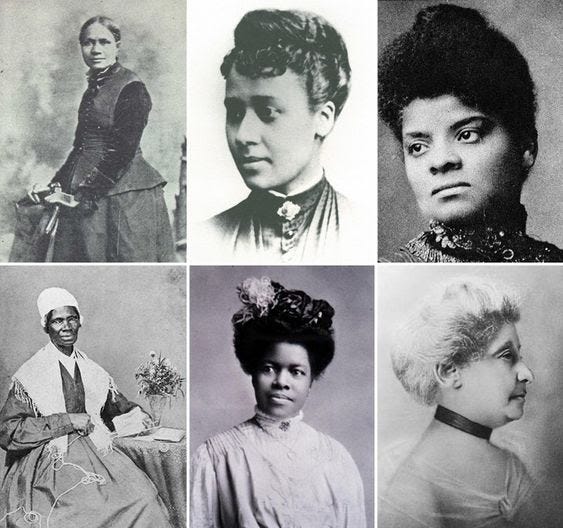

Feminists whose voices were excluded in the 1920 amendment.

Again, it’s the small stories about individual women and their personal experiences that create texture and interest to this narrative. While these bits and pieces may seem insignificant, they coalesce to create a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the conditions women were subjected to as they fought to secure the vote.

Until we regain control of our narratives by including every woman’s voice, the stories of our experiences will be shaped in ways that serve history, rather than herstory.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns of “The Danger of a Single Story,” to create stereotypes and rob people of their dignity. In her words, stories are so important that we should demand to hear more than one version because “Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

By taking back narrative control, we can weave together a more inclusive and accurate representation of our experience in the world. We enrich the collective understanding and, in the process of telling the story, we empower ourselves. We become as we write and share our stories. We discover our voices and reclaim our agency.

I’d like to suggest that we do this in community, where we can start by identifying the spaces where we’ve been silenced, name the powers that have been in charge of writing dominant narratives, and learn to resist the imposition of single, official stories which have silenced us.

In community, we can affirm one another’s experiences and create a language that captures what it’s like to exist in this world in a woman’s body. We free ourselves from narratives that feel prescriptive. We may even come to recognize how we have been complicit in our own silencing by accepting the official stories over our own.

Unsilencing ourselves is a massive undertaking, one that author Rebecca Solnit explains is too large to do alone.

“Silence is the ocean of the unsaid, the unspeakable, the repressed, the erased, the unheard. It surrounds the scattered islands made up of those allowed to speak and of what can be said and who listens. Silence occurs in many ways for many reasons; each of us has his or her own sea of unspoken words.”

Continuing to swim in this ocean is not possible. We cannot see our way through the water unless we open our eyes to see across the waves. We can do this. Together.

We can turn to our sisters, such as Malala for inspiration. Now an international speaker and activist for the education of women, Malala refused to be silenced by those who attempted to murder her; indeed, the attack amplified her message of equality and opportunity. She has said, “I am Malala. My world has changed but I have not.”

And, while we do not have the story of Joan of Arc, told in her own words, author Perdita Finn writes that Joan used her trial as a forum to convey her powerful message. “The great irony is that the Church in trying to suppress her power ended up capturing the authenticity of her voice. It was that voice—defiant, witty, wise, and deep—that caused people through the centuries to fall in love with her. Not because she liberated Orléans but because she got powerful men to shut up and listen to her.”

The very system that tried to silence Joan not only created an opportunity for her to speak, but it recorded her in historical documents, assuring that her voice would resonate across the centuries.

We cannot and should not wait to be given this chance; we need to give ourselves permission to control the narratives about our lives. By writing our own stories, we counter the forces that threaten to silence us. Following the inspiration of Joan, Malala, Inez, Ida, and the women of color who participated in the suffragist movement, we can do this.

To read more about my life as a carrier of stories, follow me at Story Carriers: The Movement. My book, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared, is available here https://a.co/d/09CV7xtq

Bravo, Jane. As Projectkin, my mission is to encourage everyone to tell their stories. Here, you’ve made a thoughtful, and truly beautiful case for why it’s so important. I can’t wait to read your book.

🥹

Can’t wait to read and share!!