Several years ago, while teaching a fiction writing course, some students in the class commented that I focused heavily on the topic of death. I protested, saying, “I don’t do that,” but when I looked over my course syllabus, the reading assignments were proof that, in fact, I was doing that. These days, it seems death is what I write about most. I do so because the way we respond to losing someone important to us is often, if not always, dismissed by a culture that pushes us to get up, move on, and get back to life afterwards.

Eventually, as writers, we must come to the page (or screen), sit alone and try to create meaning out death, an experience that, by its very nature, defies understanding. Personally, I find it to be the hardest form of writing I’ve ever attempted, not unlike rolling the Sisyphean rock up the hill, only to be knocked back by the boulder’s weight as it plummets downward again.

As a former writing professor and author, of course, I recommend writing about death.

One reason is that death is unavoidable. We will all die, and we’ll all lose people. About eight billion people are living on this planet currently and, in 2022, sixty-seven million of them died. It’s a good guess that each and every one of us has been affected by the loss of a family member or friend in the past year or so. Even with the return of relatively good health since the pandemic, the number of deaths is expected to go up in the coming decades as the population ages. As we watch genocidal wars erupt around the globe, we’re witnessing death at an exponential rate and, becoming dangerously close to feeling numbed by the reports of casualties. Another reason I suggest writing about death is so we can address our complicity in the environmental death of our world. I won’t go into the tragic ways capitalism and progress have sacrificed our planet and how we, as consumers, have contributed to its demise, but I add this to the list of reasons to write about death.

It turns out, human beings are pretty adept at losing people to death. Scientists who study animal grief have reached the conclusion that “death is one of the most severe events experienced by a social species,” and, and because our (human) survival depends on social bonds, we have evolved a fairly strong emotional capacity to cope with it.

If that’s the case, and I’m not sure I believe it, why not spend time with friends or family to help us grieve? Why isolate in a room and practice something that has the power to compound our pain? In spite of this natural ability to recover, I believe writing about death is imperative.

Poets, authors, philosophers, theologians, and other very smart people have struggled to squeeze meaning out of the anguish that overtakes us in grief, and some have written eloquently about it. But the truth is, there are no words capable of expressing the pain, agony, and distress we feel when we’ve lost someone, and no language capable of holding back the haunting emptiness that follows us for the rest of our lives.

C.S. Lewis got close to nailing down the cyclical, unrelenting experience of loss, observing, “For in grief nothing ‘stays put.’ One keeps on emerging from a phase, but it always recurs. Round and round. Everything repeats.” In The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion accuses grief of crossing emotional boundaries, almost as though it were a pushy family member. “Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life…” Perhaps it is the feeling of helplessness we find ourselves in as we watch our world explode into tiny pieces that makes us doubt our ability to capture the experience in words. And with good reason: the atomizing pain of loss defies language. Indeed, the suddenness and finality leave us in a state of silenced shock.

It has to be noted that we’re bombarded with powerful messages to avoid this kind of creative work, some so subtle we’re not aware of them. We may feel that indulging in writing about grief is holding up evolutionary progress of the species by focusing on pain. Author Maria Popova observes that although expressing our loss in an artistic piece of prose or poetry may help relieve some of our suffering, it could be counterintuitive to our survival as human beings. That might seem shocking, but Popova argues that what we need is to survive this life, which is not the same thing as becoming immortal.

“We dream of immortality because we are creatures made of loss — the death of the individual is what ensured the survival of the species along the evolutionary vector of adaptation — and made for loss:” Her caution suggests we face a tension between our private torment and a shared terror of extinction.

Right up there with Popova’s warning is the danger that grief can become so complex that writing may exacerbate worry about the end of life, ushering in a malaise or dread, a way of living that is, in the words of Hannah Arendt, a kind of demise. “A love that seeks anything safe and disposable on earth is constantly frustrated, because everything is doomed to die. In this frustration love turns about and its object becomes a negation, so that nothing is to be desired except freedom from fear.” (Hannah Arendt, Love and Saint. These writers’ ideas make it clear: writing about death requires a staggering amount of emotional stamina.

As painful as writing may be, it’s not as though we can circumvent or lessen our agony by avoiding it. Mary Frances O’Connor, who studies the neurophysiology of grief explain, we are at the mercy of a brain that demands time and energy to navigate loss.

“Grief is a heart-wrenchingly painful problem for the brain to solve, and grieving necessitates learning to live in the world with the absence of someone you love deeply, who is ingrained in your understanding of the world. This means that for the brain, your loved one is simultaneously gone and also everlasting, and you are walking through two worlds at the same time. You are navigating your life despite the fact that they have been stolen from you, a premise that makes no sense, and that is both confusing and upsetting.” Grief is complicated and, often, extended by the fact that we are stuck, waiting for the brain to re-map as we try to keep our heads above the rising tide of agony.

If writing stimulates the brain to begin this necessary cognitive work, it may also push us to ask important questions about the way death is interpreted in the Western world, where we tend to see it as a stop on the journey to an idealized destination. Personally, I’m drawn to the Eastern philosophy that offers a longer version of life, an extended warranty, as it were. In fact, I think it’s rather cruel to make us feel like we’re given one chance on this ride around the sun and told to get off the merry-go-round when the operator brings it to a halt.

You don’t have to agree with me but consider the possibility that death has been packaged and sold to us in a way that meets the needs of a culture dependent on progress. Maybe we are being commodified as champions of survival, programmed to believe grief is self-serving unless we can find a way to use it as an occasion to contribute to the economy. Death is a profitable event for the funeral industry, including florists, wreath-makers, and condolence card manufacturers. This also includes estate attorneys and insurance companies that make millions from our fear of death.

The bottom line is, we may always feel pressured to ignore our feelings so we can get back to living a so-called productive life as wage-earners and taxpayers. This may keep the population growing steadily (along with the economy) but, if we are to evolve as human beings with soul and compassion, perhaps we need to ask ourselves how we can come to terms with death in a gentler, saner way.

Recently, I wrote about the death of my sister, in my memoir, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared. While I worked on the book, I was overcome with sadness, as the memories of her sudden disappearance surfaced. I was barely two years old when she died, yet the experience felt very immediate. As soon as I wrote the first sentence about her loss, I was transported back to an early part of my life when I had no reason to suspect that someone could be ripped away or disappeared. Suddenly, the adult who was writing a book turned into a toddler who was unable to understand the permanence of her loss.

In spite of all this, I still recommend writing about death, but I want to offer a caveat to anyone who plans to do so. Writing may be a healthy practice, but it also has the power to drag us back into the initial experience of loss, which will prolong our trauma. When we write, we need to be prepared for physical pain because loss and grief are also embodied experiences. Loss causes us to walk across our days favoring the part that hurts, wondering if it is visible to the world. We worry about re-igniting the grief by simply touching a tender spot in our souls or recalling a memory of our loved one. We go out of our way to avoid stepping just the wrong way on a pebble, causing a surprise that feels akin to that of the shock of the original loss.

I always understand the choice to avoid or delay writing about loss, as much as I understand it when a writer composes pieces that fetishize or glorify grief. We all approach loss in unique and, often, confusing ways, making choices based on our tolerance for pain and suffering, the messages we receive from society, as well as the overall physical, spiritual and mental state we are living in at the time.

Given the risk of re-injury and rekindling our suffering, why do it? Why write about death? And when we hit the wall of pain that writing brings up, why continue?

Poet Maria Rainer Rilke writes about death’s power to change us, advising that, “The great secret of death, and perhaps its deepest connection with us, is this: that, in taking from us a being we have loved and venerated, death does not wound us without, at the same time, lifting us toward a more perfect understanding of this being and of ourselves.”

I’m not sure his words offer the kind of comfort most need at a time of loss, but I do consider writing to be a revolutionary gesture, an act of disengaging from a world that discourages us from spending more than a brief period of time in grief. It’s a courageous act of agency and a form of resistance to the pressures and messages that threaten to silence us.

If you are ready to write about loss, consider it as an investment in your soul. Write to build a linguistic container where grief can be held safely and gently, to be revisited at a future time when you feel strong enough to do so.

I take inspiration for writing about loss from the work of poet David Whyte, whose poem, “Farewell Letter” is written in the form of an imagined letter written by his mother after her death. The lines of the poem capture his mother’s voice.

“She begins:

Dear son

it is time for me to leave you,

the words you are used to hearing, are no longer mine to give.

You can only hear those words of motherly affection now from your own mouth and only for those who stand motherless before you.”

Whyte’s longing for his mother’s comforting voice is mixed with the realization that he can no longer turn to her for reassurance. Yet, she is present, her motherly advice echoed through the speaker’s lines in the lyrics of the poem. This piece not only honors his mother, but it also brings to life the part of her that remains, residing in his wildly poetic soul.

We write about our lost loved ones because we need more than a memory of what once was. Former Celtic poet and priest, John O’Donohue suggested writing poetry to “look into the faces of our lost loved ones, as though we could bring them back into being through music, poetry, writing. “

“Let us not look for you only in memory,

Where we would grow lonely without you.

You would want us to find you in presence”

(“On the Death of the Beloved”)

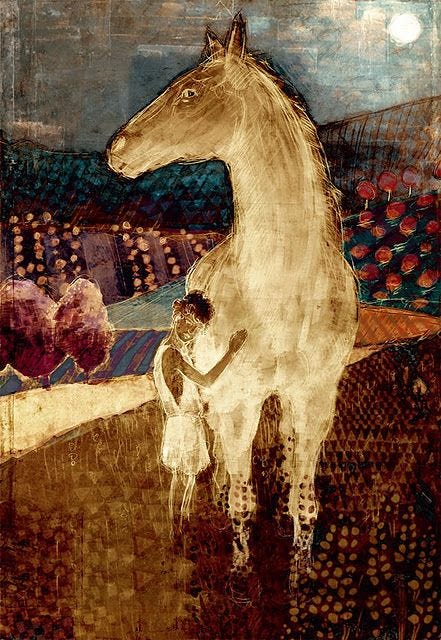

Writing is a powerful way to cope with loss, but I think we need more. We need to project ourselves back out into the world in a way that creates something beautiful out of the terrible injury inflicted on us. Something meaningful. At the very least, we can create a roadmap that illustrates our path out of the devastation, and we can do this even as we sit with our pain. The process of writing can be a metaphorical way of cooking up a medicine out of the debris of our misery, an elixir we can offer to others who are trying to survive in a burning, dying world. Writing may hurt, even briefly incapacitate us but, as Jane Hirschfield illustrates in her poem, “For What Binds Us,” we may one day be able to touch the place in our soul where it hurts most, where it feels like the skin has been ripped away,

"And see how the flesh grows back

across a wound, with a great vehemence

more strong

than the simple, untested surface before.

There's a name for it on horses,

when it comes back darker and raised: proud flesh. “

My advice to you, dear writer is to show up and write. Not with any expectation of hope, nor to avoid the darkness, the pain. Just write. As you do so, know that you are reaching out (metaphorically) to establish solidarity with others who are walking with you into the mystery that awaits.

Peace to you.

My book, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared, will be published in 2/2024 by Writing Brave Press.

My father lost a sibling of a few months old, a brother. Once while in a tender moment, he broke down over it. It was one of the few times he showed that side of himself. Writing has to be one of those surgical things you can do with yourself to release some of that hurt. Thank you for your words shared with us.

My sincere condolences to you for the loss of your sister. I have lost manyfamily members. In fact only my younger brother and I are left in our family.

I wrote about my close brothers suicidal death in one of my October sub stacks. That was the time of year he passed away. I wrote about my close brothers suicidal death and one of my October sub stacks. That was the time of year he passed away In 2008. That time of year always brings a certain type of sad anxious butterflies in my stomach. Writing about his death was a very cathartic experience for me here on Substack.

Blessings to you 🤗 ✨💫🙏