Story Carrier

Who is carrying your family’s stories? The stories carried by your mothers, grandmothers, and their grandmothers, as well as the ones carried by the ancestors you’ve never met. It’s very likely that your family is comprised of a layered narrative filled with tales of joy, grief, suffering, sorrow, and, even of remorse, all of which connect one member to the other, as artist and philosopher Maira Kalman’s poem illustrates.

Happy families,

Unhappy families.

All the same, right?

Ach. ach. ach.

To begin

You are born.

To a long line of ancestors

who are long gone

but still yell or whisper

in your ear

in the depths of night.

A game of telephone played

from one generation to the next.

Garbled and confused.

Glimmers of light.

Misunderstandings.

Errors.

And now, here you are.

With the ones you love.

Or the ones you don’t.

The ones you cannot live without.

The ones you would like to smite.

Those who have disappointed you

or betrayed you. Those who have

been kinder than you deserve. And

the kind ones who inevitably die.

And leave you feeling very much

alone. They are what you have.

And if you think, at any given point,

that you know what is going on,

you are sorely mistaken.

What is meant by her last line, which suggests that we cannot know “what is going on.” I think she’s referring to the stories that we have never been told, those stored in the marrow of our bones, passed along bloodlines. As she notes, these stories may be “garbled and confused” They could be based on “misunderstandings. Errors.” When we hear a partial family story that we are unable to verity, we may dismiss it. However, a story does not dissipate into the mist or float away into the stratosphere. It will remain within us, unseen, undetected, while carving an imprint on our conscious mind, shaping our emotions, our way of seeing the world.

Stories are a powerful form of energy, and they await the human touch to bring them into conscious awareness. If contained, or carried as secrets, they can become so forceful, they may, eventually, explode in the life of an unsuspecting family member whose choices may seem out of sync, but when viewed in hindsight, reveal themselves to be an appropriate response to a situation held within the story. In other words, their behavior may be in response to events or experiences they (and we) may not know about, within memories passed across generations.

When we try to capture our lives in words, we are often challenged by memory. Neuroscientists define memory as a product of chemical and electrical activity in the brain. But they do not believe memory is static. In fact, memory can change; it is malleable. We may remember an experience one way on a given day but recall it differently a few weeks or months later.

Kalman describes memory as “the still life of living.” Something like a snapshot or a picture. We may not always remember in full detail what has happened, but we often carry a picture of the event. And the picture is not always clear; it may seem to be an imprint.

If this is the case, how much of what we remember can be believed? How much of what we remember really happened?

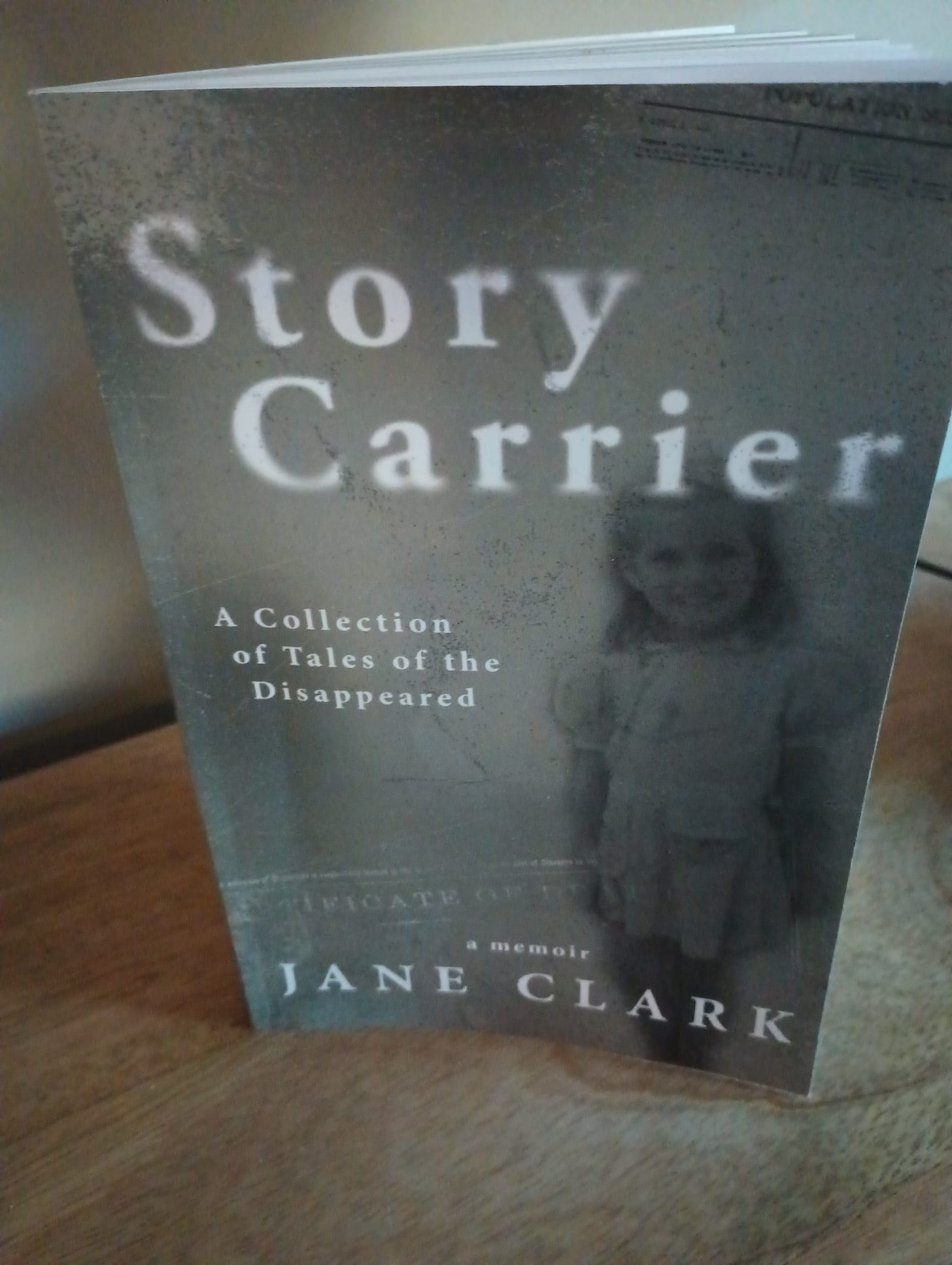

Memory challenged me when I wrote my memoir, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared. In the first chapter, I wrote about my sister’s funeral, an event I was too young to fully remember; but one that I carried in a picture, or a “still life” imprinted in my mind/soul/heart for my entire life. Using that snapshot, I interpreted the experience in the words of an adult.

Why would I choose to recall such a painful memory in my book? Because, as many artists and writers such as Elie Wiesel assert, pain and sorrow may haunt us with mental images, but we have the ability to respond with creative vitality, and to express what some have called defiant joy. When we create a work of art, such as a story, we are daring to offer more to the world. We are responding with a search for meaning and beauty.

There is, in my opinion, a piece of beauty to be found in all the stories we carry.

Untold, they may feel heavy but as we unfold parts of the tale, memories can shift, revealing pieces that escaped our attention initially. In the process, we begin to see fragments of beauty hiding beneath layers. We may begin to view the paradoxical truth that life is composed of both pain and beauty.

Taken individually, experiences may not reveal a complete story. We have to work at piecing them together in order to find an outline of an ancestral tale.

In my family, the pattern I began to see as I wrote events revealed the way women carried untold stories. We were silent about many of the most important and dramatic events in our lives and, on the surface, this created the image of a tragic set of tales. Once I was able to stand back and view everything from a distance, my perspective changed and that altered my memory.

For example, when I discovered the untold stories that influenced my mother’s beliefs about parenting, her behavior seemed understandable—-even if not totally acceptable to me and I began to see our relationship in a new light, which altered my memories of her.

Although recalling painful events is not always comfortable, ignoring them may result in physical symptoms. As writer Jeannine Oullette explains, “Our bodies remember. Our cells hold records of the past, awareness of the present, and imaginings of the future. These embodied sensations form the basis of writing that electrifies the primal exchange we continually experience with the world.” So, whether we use language to express ourselves or not, our stories will convey who we are and what we have lived. Even when we try to suppress the stories, they will communicate their presence.

Carried in an untold state, stories may continue to harm us. In particular, carrying untold secrets, as many know, is toxic. The act of carrying them becomes a form of trauma that adds to our suffering. The stories and the memories created by secrets will never go away. Your job as a story carrier is to open yourself up, to allow the stories to discover you so you can bring them into being.

When you write your life story, try to capture individual pieces, including the tiny, often fractured bits contained in your imagination. After you have written, stand back and look at the overall picture painted by the tale.

You can order my book, Story Carrier: A Collection of Tales of the Disappeared, at a.co/d/3J5Wnzy.

Follow me at Story Carrier

Thankyou.. it was my increasing awareness of Suffolk accents, where Dad came from and my need to know just where in Suffolk people hailed from that set me on a quest to find his relatives.

When I saw the film The Dig, featuring Sutton Hoo and genuine accents of that era, I dissolved into tears. Gruff yet gentle, grounded in the soul. His tweed accent. It's in my heart

Good morning.

Thankyou for sharing. It's very affirming. My own families journey revolves around loss, rejection too. Having lost my Dad at 4, I see an obituary telling me I was a chief mourner at his funeral, but have no recollection of it and very little of him, but know his loss has underscored my entire life.